by Matt Zia

We were way off the map and everything felt like shooting from the hip.

Spencer Gray and Rushad Nanavatty texted me in April with a photo of one of the most beautiful mountain faces I’ve seen and a cryptic, “expedition this fall?” Until recently, the peaks of Sikkim in NE India have been largely closed to foreign expeditions thanks to a convergence of Chinese border posturing, staunch Lepche culture, and local politics. On the most recent list of open and unclimbed peaks from the IMF, Kirat Chuli goes by the Western name of “Tent Peak'' and is seemingly another 7362m metamorphic peak on the long ridge north of Khangchendzonga. Thankfully, Spencer is better at mountain research than anyone else I know, and after finding a geologic analysis of the Eastern Himalaya and Khangchendzonga massif, and contacting the photographer from the 1993 Japanese expedition, he was confident the north buttress had a band of leukogranite worth flying halfway around the world to attempt a climb.

To even get our permit approved, Spencer had to cross reference both the IMF and Sikkimese list of open peaks. Without accurate mapping, I had to find satellite imagery and DEM models to supplement a set of 1:150,000 scale Swiss-made maps from the 70s. Even after getting all the correct papers and permits, I got my passport and visa back from the consulate less than 24 hours before my flight after the consulate mistakenly tried to give me a “missionary” instead of “mountaineering” visa, and Rushad (and 29 others) missed his flight from Amsterdam to Delhi after standing in a security line for over four hours due to only 3 out of 12 working x-ray machines.

In a reminder of geopolitical forces at play, the flight path from Amsterdam to Delhi wove between combat zones. Rather than the smooth Great Circle arc typically traced by international flights, the flight made a giant s-turn between Europe and India, detoured south to avoid Ukraine and the Russian invasion and then back north to skirt Afghanistan. Insulated from active war zones by two oceans, a desert, and a steady stream of click bait headlines, it’s too easy to pretend in America that authoritarianism ended with the fall of the Berlin Wall. While international travel for exploratory alpinism is a luxury, experiences around the world remind us how precious freedom of thought and movement really are, and how easily they come under attack, both at home and abroad. Climbing itself won’t save the world, but the experiences with different cultures, the closeness we develop with our partners, and the shared desire to protect wild places just might. If we can relay just a fraction of the humanity we learn from the people with whom we share these experiences in the mountains, maybe we can sprinkle that into the rest of our lives and create a positive ripple effect in our communities.

After a few more grey hairs resulting from the visa and permit stress, and subsequent 30+ hours of airplane and airport purgatory, I wasn’t sure if I had walked out the door of the Delhi airport or straight into a wall. Even at 4am the heaviness of the humidity was overpowering. Used to melting at a high of 85F in Montana, the 100F and 90% humidity just about knocked me on my ass, right in front of a crowd of Indian taxi drivers yelling in Hindi and trying to load my bags into their car before I was able get a ride to our friend Aftab’s house where we all commenced unpacking and repacking for the first of many times.

Like most alpine climbing teams, we skipped town out of Delhi as fast as possible once our required IMF meeting was finished. Another flight and sweaty SUV ride brought us to Gangtok, capital of Sikkim, a city of 100,000 people perched on a mountainside where every road carries on in a series of impossibly steep switchbacks, drivers expertly shifting gears through the maze of people, motorcycles, stray dogs, and overloaded trucks. After meeting with Tshering Dorjee Bhutia, our local logistics and tour operator, and spending a day checking every shop in Gangtok for batteries, fuel cans, and peanut butter, we were up until after midnight carefully repackaging our food and expedition gear. With a crew of mostly Rai porters from Darjeeling, six weeks of food, and a vague sense of how far we could drive, we caravanned north from Gangtok along roads cut into mountain sides so steep we couldn’t see the bottom of the river valley. Prayer flags worn white from a thousand years of inhabitation marked the path, the road following ancient travel routes the Lepche used moving down-valley as we climbed from the low point of Sikkim at 920’ towards the town of Lachen at 8,838’ and finally crested a pass above Thengdu at more than 18,000’.

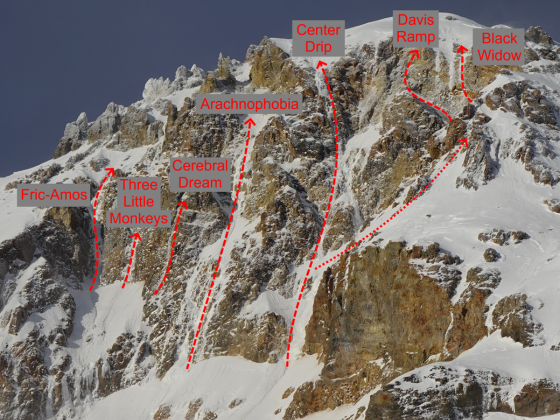

As we passed through Thengdu, the landscape changed from the lush jungle to the arid Tibetan plateau. Steep water carved walls gave way to broad glacial valleys, the landscape opened up and the deep blue Tibetan sky dominated the field of view. Cloud banks scuffled across the ridge lines, concealing the jagged maw of cirques as we wound our way up a newly built Indian Army road. Patches of fresh pavement were interspersed with long stretches that hadn’t ever seen the blade of a grader. Our hearts leapt and we all got a shot of adrenaline as we caught a glimpse of Kirat Chuli on the western horizon, after so many months of planning, training, and preparation, none of us were quite ready to believe that we were on the way, let alone seeing the mountain with our own eyes. Spencer’s hunch was right - a buttress of grey leukogranite soared above the Changsang Glacier, plastered with tendrils of ice and snow, flaked on each side by seracs but itself mercifully sheltered by the convexity of the face

The team in front of Kirat Chuli Photo: Spencer Gray

A week later, after a snow leopard sighting and shuttling several hundred pounds of food and equipment over a raging glacial creek and up the Changsang Valley, the porters left for Gangtok and we were alone, blinking in the raging Himalayan sun in basecamp at 17,500’ on the last patch of grass before the valley turned to a shattered moonscape of receding glacier. With an opportunity to ground-truth the digital maps we relied on, we quickly discovered the rate of glacial recession and formation of glacial lakes far outstripped even the maps and satellite imagery we had used to plan our trip. Where our maps showed flat glacier we found a mile-long lake, deep turquoise and filled with ice bergs calved off the receding edge of the glacier.

My friend CJ lent us a dome tent which proved to be key for morale in the coming weeks while storm-bound and restless, but in the post-monsoon sun, we were just excited for the shade and a chance to see each other without sunglasses. Motivated, we dove into climbing prep, eagerly scanning the ice-plastered North Buttress of Kirat Chuli for a climbable line and debating what and how much gear to bring. At 17,500’ basecamp, acclimatization and recovery were long, leaving plenty of time for books and music and I blasted through my downloaded collection in our first week. Thirty years after Mark Twight decreed it was bad style to run out of walkman batteries, I was thankful for lightweight solar panels and battery banks to keep my phone running through repeated rounds of the Rolling Stones. Gimme Shelter is still the best alpine climbing song ever recorded. Which version specifically is open for debate.

Expedition base camp life settled into the rhythm of the day; wake up, pound cups of strong black coffee through the black kerosene smoke in the cook tent, walk, slowly, uphill with a load, gasp for breath, descend, repeat. Left with a 10 pound bag of atta flour, I experimented to make roti and crepes. Rushad proclaimed the roti excellent, and we devoured it daily with a daal recipe received via inReach from his mom.

We spent almost four weeks traveling up and down the glacier and moraine, finding a path to a tarn at almost 19,000’ for advanced base camp. Each trip stole a bit more of our fitness, boulder hopping for hours through the fresh talus, gingerly testing every step while we waxed about the place of alpine climbing in our lives, our risk tolerance for big alpine routes, and friends lost too soon to the mountains. Heavy for an expedition, but balanced by the levity of days spent lounging in fields of Himalayan wildflowers, drinking straight from mountain springs, and sightings of a Tibetan Griffon and a flock of Himalayan Snowcocks that seemed to waver between curiosity of the strange beings and enormous yellow dome suddenly inhabiting their meadow and sheer terror of these unknown lifeforms.

By mid-October we ran out of books and it was time to launch. Our hoped-for weather window was fleetingly small. Six days, at most, of clear and cold before the jet stream descended south over the Himalaya and, in all likelihood, slammed the door shut on the autumn climbing season. We repacked one final time and zipped the tents behind us. Rushad’s and my packs weighed 30 pounds. Spencer, at over 6 feet tall with size large and XL layers jokingly cursed us under his breath as his flirted with 35. Launching on an unclimbed aspect of a 7362m peak with such a tiny pack feels ludicrous.

At dawn of the next day, we fought soul-destroying snow conditions across the Changsang Glacier, knee to thigh deep facets with a double breakable crust. A pitch above the bergschrund, the crust abated, only for two feet of dry facets to take its place. The early winter storms that trapped us in basecamp deposited a sheen of sugar across the face, unconsolidated and rotten in the frigid Himalayan night and untouched by the warmth of the sun. By twilight, Rushad gracefully tapped his way up a delicate, delaminating slab of ice. He told us later that was the hardest pitch of ice he’s climbed in his life.

Rushad leading an ice pitch on day one, N. Buttress, Kirat Chuli Photo: Spencer Gray

I led into the night, searching for any semblance of a bivy. With few options in range of my headlamp, I found a patch of workable ice, built a nest of our remaining ice screws and brought Spencer and Rushad up. Hours of digging on the snow cone and backfilling our homemade ice hammock resulted in a miserable half seated bivy ledge. We crawled into the tent and tried to sleep, feet dangling in space and backs against a stream of spindrift.

Our first "bivy". The ice hammock was essential. Photo: Spencer Gray

In the middle of the night my stomach revolted against the dehydrated meal. Of course I was furthest into the tent. I unleashed a stream of profanity as I desperately lunged for the door and unloaded half my dinner into the snow outside. Valuable calories I wasn’t getting back, but without a load of rehydrated mushroom risotto, my stomach calmed and I was able to rest the remainder of the night. In the morning, Spencer and Rushad asked if I was okay. I told them I was fine, choked down a granola bar and cup of hot water, and tied into the rope. Rushad nodded and Spencer grabbed the rack and led off around a corner.

As the second twilight caught us, it was clear we were in a bail now or bail later situation. Protection was few and far between, every move required full excavation of the faceted snow, and there was no chance of anything resembling a bivy. Between the snow, cold, a broken ice tool, and impending storm, each additional step put us closer to the edge. The decision took all of a couple seconds. We rappelled through the night, leaving a trail of naked v-threads and pins behind as we raced for flat glacier and a chance to lay down.

The sun finally hit the glacier and our tent mid-morning the next day and we bantered about our next move.

“Warm and flat…this is nice”

“I hear Texas is warm and flat. I’m moving there.”

“What about San Diego?”

With the weather window closing, Spencer and Rushad decided to make one more attempt on Langpo South (pt 6857m). Earlier we acclimated on the lower slopes in a short weather window. Now, turned around from Kirat Chuli, the two of them revisited the idea of Langpo South and packed their bags for an attempt. For myself, I elected to stay at basecamp, monitoring the inReach. In environments like alpine climbing with imperfect and incomplete information, I think all we can do is make educated decisions based on our own risk tolerance and the best information available. With Kirat Chuli off the table, Spencer and Rushad made their decision, I made mine, and having the capacity to accept without judgement the decisions of teammates is a hallmark of a quality expedition.

The next day the temperature dropped and the winds built. At basecamp I was cold. At over 6000m, Spencer and Rushad were colder. Keeping the rope stashed to keep moving and stay warm, they followed 70° ice up the south face to the southwest ridge and the summit. The following morning, Spencer texted from the glacier that they were safely down and headed back my way after making the second known ascent of Langpo South.

Group photo with the local Indian Army unit. After their initial confusion about an Indo-American climbing team, the unit was insistant on shaking hands and taking group photos after dark Photo: Matt Zia Collection

After arranging pickup with Tshering, all we had was to sit and wait for the porters to show up before the next winter storm shut the pass back to Thengdu. After a morning of hurriedly packing up camp and arranging loads, we all threw packs on our backs and raced downhill to the pair of waiting trucks as a dark cloud enveloped Kirat Chuli behind us. Night and the storm caught us before the pass, but the Indian Army unit posted in the valley still insisted on taking a group photo before they raised the gate and let our driver pick his way up the intermittent pavement. Smashed in the middle seat in back, all I could see was the road ramped up ahead of us as we climbed the pass to the top. The only time I couldn’t see road is when the hillside fell away at a switchback. The old SUV strained around corners and rumbled on. I felt more than heard the shifting of gears and rush of RPMs as the driver smoothly flowed from 1-2-3-2-3-2-1-2-3 and back. At 18,000’ the angle of the SUV dropped and we all turned to make sure the second truck made it over behind us, cheering as two pairs of headlights tilted and began descending towards Thengdu, and eventually Gangtok, Delhi, and home.